The 'cloud' is a real buzzword these days, but what exactly is the cloud, how does it impact what you do, and is it anything really new?

"What's the cloud?" "Where is the cloud?" "Are we in the cloud now?!" These are all questions you've

probably heard (and not just from Amy Poehler in

Best Buy's Super Bowl ad) or even asked yourself. The term "cloud computing" is everywhere. Let's explain further.

In the simplest terms, cloud computing means storing and accessing data and programs over the Internet instead of your computer's hard drive. The cloud is just a metaphor for the Internet. It goes back to the days of flowcharts and presentations that would represent the gigantic server-farm infrastructure of the Internet as nothing but a puffy, white cumulonimbus cloud, accepting connections and doling out information as it floats.

What cloud computing is not about is your hard drive. When you store data on--or run programs from the hard drive, that's called local storage and computing. Everything you need is physically close to you, which means accessing your data is fast and easy (for that one computer, or others on the local network). Working off your hard drive is how the computer industry functioned for decades and some argue it's still superior to cloud computing, for reasons I'll explain shortly.

The cloud is also not about having a dedicated hardware server in residence. Storing data on a home or office network does not count as utilizing the cloud.

For it to be considered "cloud computing," you need to access your data or your programs over the Internet, or at the very least, have that data synchronized with other information over the Net. In a big business, you may know all there is to know about what's on the other side of the connection; as an individual user, you may never have any idea what kind of massive data-processing is happening on the other end. The end result is the same: with an online connection, cloud computing can be done anywhere, anytime.

Consumer vs. Business

Let's be clear here. We're talking about cloud computing as it impacts individual consumers—those of us who sit back at home or in small-to-medium offices and use the Internet on a regular basis.

There is an entirely different "cloud" when it comes to business. Some businesses choose to implement Software-as-a-Service (SaaS), where the business subscribes to an application it accesses over the Internet. (Think Salesforce.com.) There's also Platform-as-a-Service (PaaS), where a business can create its own custom applications for use by all in the company. And don't forget the mighty Infrastructure-as-a-Service (IaaS), where players like Amazon, Google, and Rackspace provide a backbone that can be "rented out" by other companies. (Think Netflix providing services to you because it's a customer of the cloud-services at Amazon.)

Of course, cloud computing is big business: McKinsey & Company, a global management consulting firm, claims that 80 percent of the large companies in North America that it's surveyed are either looking at using cloud services—or already have. The market is on its way to generating $100 billion a year.

For a great look at more examples of business services in the cloud, read

PCMag's 20 Top Cloud Services for Small Business.

Common Cloud Examples

The lines between local computing and cloud computing sometimes get very, very blurry. That's because the cloud is part of almost everything on our computers these days. You can easily have a local piece of software (for instance, Microsoft Office 365, one of the versions of Office 2013) that utilizes a form of cloud computing for storage (Microsoft Skydrive in the case of Office). That said, Microsoft also offers a set of Web apps that are close versions of Word, Excel, PowerPoint, and OneNote that you can access via your Web browser without installing anything.

Some other major examples of cloud computing you're probably using:

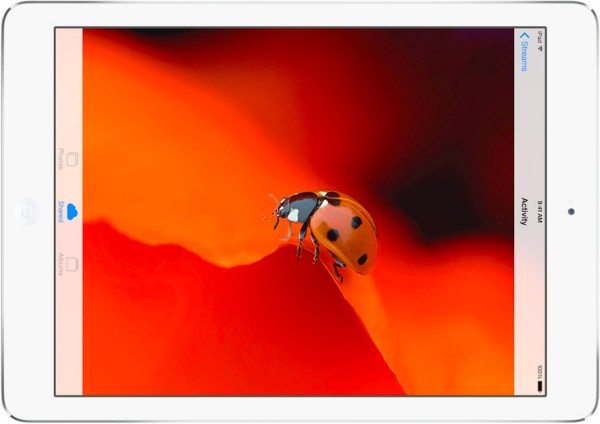

Google Drive: This is a pure cloud computing service, with all the apps and storage found online. Drive is also available on more than just desktop computers; you can use it on tablets like the iPad$599.99 at Amazon or on smartphones. In fact, all of Google's services could be considered cloud computing: Gmail, Google Calendar, Google Reader, Google Voice, and so on. Upgrade to Google Apps and you can use many of the above with your own domain name attached.

Apple iCloud: Apple's cloud service is primarily used for online storage and synchronization of your mail, contacts, calendar, and more. All the data you need is available to you on your iOS, Mac OS, or Windows device. iCloud also stores media files.

Amazon Cloud Drive: Storage at the big retailer is mainly for music, preferably MP3s that you purchase from Amazon.

Hybrid services like Box, Dropbox, and SugarSync all say they work in the cloud because they store a synched version of your files online, but most also sync those files with local storage. Synchronization to allow all your devices to access the same data is a cornerstone of the cloud computing experience, even if you do access the file locally. Likewise, it's considered cloud computing if you have a community of people with separate devices that need the same data synched, be it for work collaboration projects or just to keep the family in sync. For a huge list of cloud-based Web apps, check out the Best Free Web Apps.

Cloud Hardware

Right now, the primary example of a device that is completely cloud-centric is the Samsung Chromebook Series 3, an inexpensive laptop that has just enough local storage and power to let it run a Web browser, specifically Google Chrome. From there, most everything you do is online: apps, media, and storage are all in the cloud.

Of course, you may be wondering what happens if you're somewhere without a connection and you need to access your data. This is currently one of the biggest complaints about devices like the Chromebook, although their offline functionality is expanding.

The Chromebook isn't the first product to try this approach. So-called 'dumb-terminals' that lack local storage and connect to a local server or mainframe go back decades. The first Internet-only product attempts included the old NIC (New Internet Computer), the Netpliance iOpener, and the disastrous 3Com Audrey. You could argue they all debuted well before their time—after all, dial-up speeds of the 1990s had training wheels compared to the accelerated broadband Internet connections of today. That's why many would argue that cloud computing works at all: the connection to the Internet is as fast as the connection to the hard drive.

Or is it?

Arguments Against the Cloud

In a recent edition of his feature "What if?", xkcd-cartoonist (and former NASA roboticist) Randall Monroe tried to answer the question of "When—if ever—will the bandwidth of the Internet surpass that of FedEx?" The question was posed because no matter how great your broadband connection, it's still cheaper to send a package of hundreds of gigabytes of data via Fedex's "sneakernet" of planes and trucks than it is to try and send it over the Internet. (The answer, Monroe concludes, is the year 2040.)

Cory Doctorow over at boingboing took Monroe's answer as "an implicit critique of cloud computing." To him, the speed and cost of local storage easily outstrips using a wide-area network connection controlled by a telecommunications company—your ISP.

That's the rub. The ISPs, telcos, and media companies control your access. Putting all your faith in the cloud means you're also putting all your faith in continued, unfettered access. You might get this level of access, but it'll cost you. And it will continue to cost more and more as companies find ways to make you pay by doing things like metering your service, where the more bandwidth you use, the more it costs.

Maybe you trust those corporations. That's fine, but there are plenty of other arguments against going into the cloud whole-hog. Apple co-founder Steve Wozniak has decried cloud computing: "I think it's going to be horrendous. I think there are going to be a lot of horrible problems in the next five years." In part, that comes from the potential for crashes. When there are problems at a company like Amazon, which provides cloud storage services to big name companies like Netflix and Pinterest, it can take out all those services (as happened in the summer of 2012).

But mostly, Wozniak was worried about the intellectual property issues. Who owns the data you store online? Is it you or the company storing it? Consider how many times there's been widespread controversy over the changing terms of service for companies like Facebook and Instagram—which are definitely cloud services—regarding what they get to do with your photos. Ownership is a relevant factor to be concerned about.

After all, there's no central body governing use of the cloud for storage and services. The Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) is trying, having created an IEEE Cloud Computing Initiative in 2011 to establish standards for use, especially for the business sector. But otherwise, cloud-computing—like so much about the Internet—is a little bit like the Wild West, where the rules are made up as you go, and you hope for the best.

14:05

14:05

Admin

Admin